Additional Vital Signs: Blood Pressure

The skill of taking a blood pressure is typically seen as the preserve of doctors and nurses rather than first-aid providers. In a remote environments, the ability to take a blood pressure can add another dimension to your casualty assessment.

In this video you will learn what blood pressure is, how we measure it and why it is useful.

Taking a Blood Pressure

Have the casualty sat down and relaxed.

If the first reading is suspiciously high, it may be worth taking it two or three times. "White coat syndrome" is the psychosomatic response raising blood pressure because the casualty is anxious. It may lower to a more reasonable level in consecutive measurements.

Typically the left arm is used. If this is not possible because you don't have access to the casualty's left arm (they are on a stretcher in a vehicle for example) use the same arm for each measurement for continuity. Document which arm was used e.g. 118/86 (R) or 118/86 (L).

If the casualty is laying down - record this this as well. e.g. 118/86 (laying down) or (supine) or (recumbent).

With any patient suffering chest pain there may be benefit recording the blood pressure in both arms as significant differences between the left and right arms could indicate left ventricular failure or aortic dissection.

The arm should be extended, but relaxed.

Identify the brachial pulse on the inside of the elbow.

Wrap the cuff around the casualty's arm, over the bicep - not too low.

Position the "Artery" marker over the brachial artery, above where you felt a pulse. If you cannot feel the pulse, place the marker where you would expect to feel it.

Inflate the cuff either:

With a couple of fingers on the pulse, until you cannot feel the pulse or

to 200 mmHg if you are in a rush.

Place the diaphragm of the stethoscope over the brachail artery - where you felt the pulse.

Gradually release the air from the cuff and listen for the first sound - this is the systolic blood pressure.

Continue to release the air - the sound should get louder and then quieter - the point at which you last heard a sound is the diastolic blood pressure.

Deflate the cuff all the way and record your findings before you forget!

Tips to make life easier

Taking a blood pressure is a skill. It is not a technically difficult skill but it takes practice. One of the hardest aspects is actually listening for those sounds.

If using a dual head stethoscope, the most common reason you cannot hear anything is because you are listening to the bell not the diaphragm. Always check before you use the stethoscope.

Position the stethoscope ear-pieces forward so that they are in line with the ear canal.

Position the cuff high enough so the diaphragm is not tucked under it. The stethoscope will pick up every movement of the cuff which creates background noise.

Sometimes the tubes from the BP cuff clatter over the stethoscope tubing creating additional noise. A BP cuff can be put on upside-down which repositions the cuff tubes and may keep them away from the stethoscope tubing. Just make sure the "Artery" marker is still over the brachial artery (it will now be pointing to the top of the arm, the brachial artery can be found between the bicep and the tricep near the armpit.

In a noisy environment, such as inside a moving vehicle:

Lift your heals off the floor to prevent noise transfer through your body.

Support the causality's arm under the elbow to lift it off the seat/stretcher.

Try listening with the bell instead of the diaphragm.

Good quality stethoscopes help but are not essential. A cheap plastic set will do you no favors but basic stethoscope for less than £30.00 is fine for the occasional user or team medic bag. Unless you are able to interpret cardiac and respiratory sounds there is no need to spend more than this.

Practice.

Systolic & Diastolic Pressures

The systolic and diastolic values alone will give an overall view of the casualty's state of health. Normal blood pressure is between 100-140 / 60-90.

Blood pressure changes minute-by-minute and follows circadian rhythms; blood pressure is highest in the morning and evenings and lowest while sleeping. If the casualty is not time critical or if you are monitoring a casualty, checking blood pressure several times will show an average and a trendthat can be more useful than that first baseline measurement. Blood pressure will also changedue to anxiety, stress, after eating and with exercise. Consider these variables or rule them out.

Blood pressures below the normal ranges are considered hypotensive - the casualty is suffering from hypotension. For extremely fit people low blood pressure can be normal. Low blood pressure can be attributed to 'standing up too quickly', which is benign or the life threatening hypovolaemic shock.

Other causes include:

Anaemia

Hypovolaemia - not just blood loss but all fluids including dehydration, vomiting and diarrhoea

Medication - beta blockers, antidepressants

Existing heart conditions including congestive heart failure

Sepsis

Values above 140/90 indicate the casualty maybe hypertensive. High blood is most usually linked to lifestyle factors such as diet, obesity, smoking and drinking alcohol. All of these factors are known risk factors for developing hypertension. Age and genetics (unchangeable) also influence the development of hypertension. High blood pressure can also be caused by:

High blood pressure can also be caused by:

Acute pain

Pregnancy and birth control medication

Chronic kidney disease

Hormonal disorders - hypo/hyperthyroidism

Prescription and recreational drugs (particularly stimulants)

| Category | Systolic mmHg | Diastolic mmHg |

|---|---|---|

| Critical Hypotension | Look at the Mean Arterial Pressure | Look at the Mean Arterial Pressure |

| Hypotension | <90 | or <60 |

| Healthy | 90-119 | and 60-79 |

| Acceptable | 120-139 | and 80-89 |

| Hypertension | >140 | or >90 |

| Critical Hypertension | >180 | or >110 |

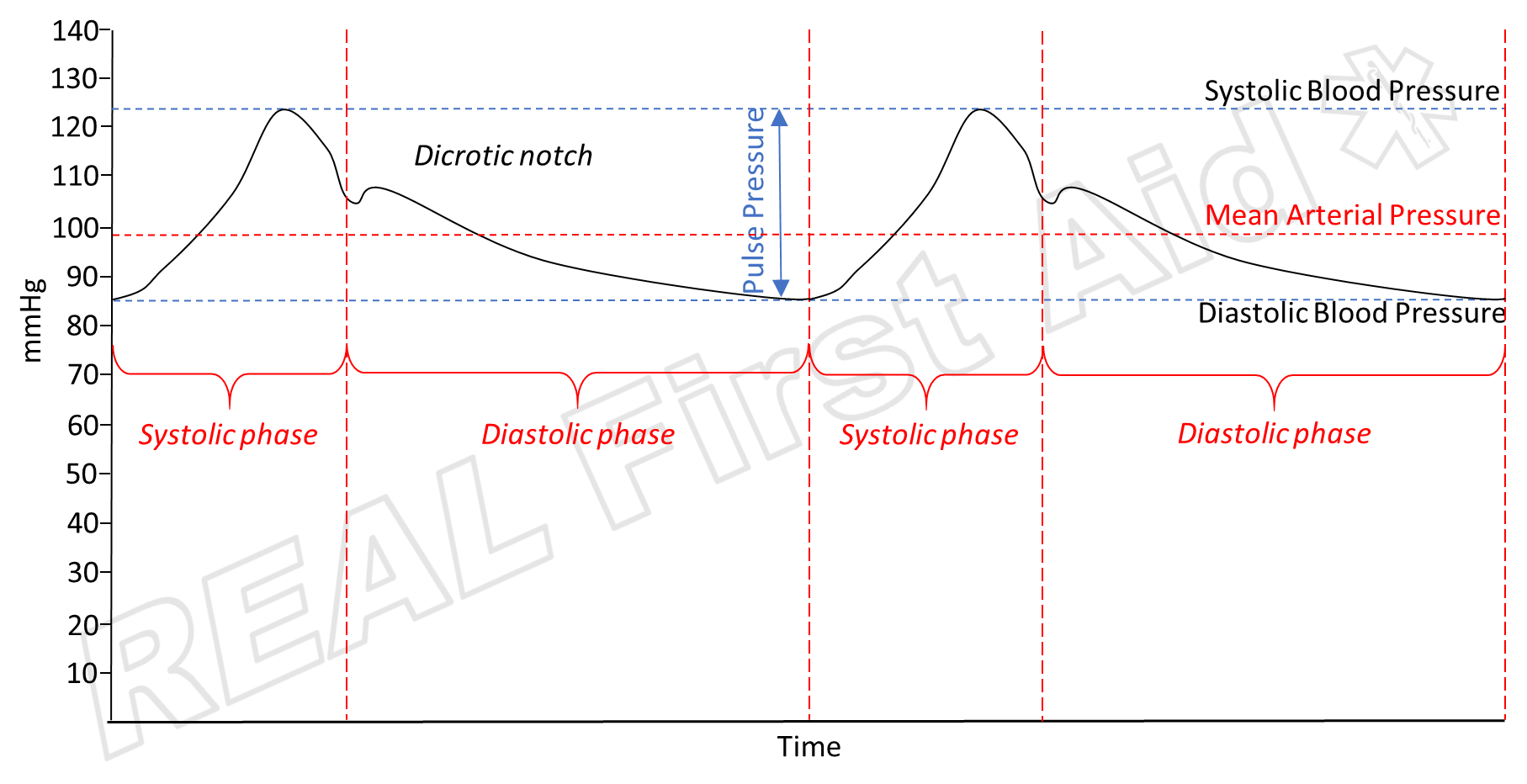

Pulse Pressure

If the casualty's blood pressure is not normal for them and lifestyle factors have been ruled out, looking at the pulse pressure can sometimes point to other issues.

Pulse Pressure = Systolic Pressure - Diastolic Pressure

A “low” number indicates a narrow pulse pressure. A high number indicates a wide pulse pressure.

A trauma casualty with a narrow pulse pressure can indicate significant blood loss (low cardiac output) or cardiac tamponade (a life threatening condition where bleeding within the sack that surrounds the heart increases pressure to the point that the heart cannot beat).

A narrow pulse pressure in a non-trauma casualty can also indicate congestive heart failure or aortic valve stenosis (narrowing of the aorta / aortic valve, reducing blood flow out of the heart).

Wide pulse pressures may indicate:

Aortic regurgitation

Fever / infection

Anaemia

Raised intercranial pressure – due to infection, head injury or High Altitude Cerebral Oedema

Pregnancy

| Casualty | Trauma | Medical |

|---|---|---|

| Hypertension | Acute pain Head injury |

Acute pain Hormonal illness Kidney disease Lifestyle Medication /drugs Pregnancy |

| Hypotension | Hypovolaemia | Anaemia Anaphylaxis Heart conditions Medication Sepsis |

| Wide Pulse Pressure | Head injury | Altitude illness Anaemia Aortic regurgitation Fever / infection Pregnancy |

| Narrow Pulse Pressure | Cardiac tamponade Hypovolaemia |

Aortic valve stenosis Congestive heart failue,/td> |

Mean Arterial Pressure

The mean arterial pressure (MAP) is an estimated average blood pressure as an indication of perfusion - how much oxygen is being provided to the tissues of the body.

Mean Arterial Pressure provides a more comprehensive and accurate indicator of how well the patient is perfusing (1) and can be a more reliable indicator of a rapidly deteriorating casualty (2)

It is calculated as either:

(Diastolic Pressure + Diastolic Pressure + Systolic pressure) / 3

1/3 Pulse Pressure + Diastolic Pressure

This can be a bit of headwork when you have enough going on with your casualty. There's a bunch of apps to help you quickly work it out but every smartphone will have a calculator and it is not a difficult calculation.

MAP is not worked out for all casualty's, only those whose perfusion we are concerned about. This includes:

Hypovolaemic Shock

Anaphylactic Shock

Stroke

Sepsis

Head injury

Shock Index

The shock index (SI) is a bedside assessment defined as heart rate divided by systolic blood pressure, with a normal range of 0.5 to 0.7 in healthy adults.

Experimental and clinical studies have shown that SI is linearly inversely related to physiologic parameters, such as cardiac index, stroke volume, left ventricular stroke work, and mean arterial pressure. (3) A SI ≥ 1.0 has been associated with significantly poorer outcomes in patients with acute circulatory failure (3, 4). Furthermore, SI was also shown to indicate persistent failure of left ventricular function during aggressive therapy of shock patients in the ED. (5) In 1994, Rady et al (6) found that a SI ≥ 0.9 predicted higher illness priority at triage, higher hospital admission rates, as well as intensive therapy on admission than pulse or blood pressure alone. This suggests that SI may be a valuable tool for the early recognition and evaluation of critical illness in the ED (6), as well as a means to track the progress of resuscitation. (5)

Further reading - Shock

Summary

| Reference | Value |

|---|---|

| Normal Systolic | 100 - 140 |

| Normal Diastolic | 60 - 90 |

| Pulse Pressure | 30 - 40 |

| Mean Arterial Pressure | 65 - 110 |

| Shock Index | 0.5 - 0.7 |

As with all Vital Signs, blood pressure is looked at as part of the bigger picture. A low or high blood pressure may be perfectly normal for that individual, and if all of their other vital signs are normal, this is not necessarily anything to worry about.

If abnormal blood pressure values are found but their other vital signs are normal, rule out lifestyle factors before panicking about life-threatening conditions.

Consider what type of casualty are you dealing with. Interpreting the blood pressure, pulse pressure and MAP will have different meanings depending upon whether they are trauma or medical ( Injured or Ill ).

Record your findings accurately and promptly. Even if the numbers you get don't mean anything to you, pass the information on if you are using telemedicine and upon handover. Blood pressure recordings, especially trends. can mean a lot more to a professional. The longer your data set of trends the better. Without this the next level of care has to start their recordings (and search for trends) from scratch.

Practice!

Special thanks to Billy Doyle of Resuscitation Skills.

Next Article - The Art of Questioning - SAMPLE

References

Henry JB, Miller MC, Kelly KC, Champney D. (2002) “Mean arterial pressure (MAP): an alternative and preferable measurement to systolic blood pressure (SBP) in patients for hypotension detection during hemapheresis”. Journal of Clinical Apheresis. 17(2):55-64

Heal M, Silvest-Guerrero S and Kohtz C (2017) “Design and Development of a Proactive Rapid Response System”. Computers, Informatics, Nursing. 35(2): 77-8

Rady M, Nightingale P, Little R, et al. (1992) “Shock Index: A Re-evaluation in Acute Circulatory Failure”. Resuscitation. 23:227–234.

Al Aseri Z, Al Ageel M, Binkharfi M. (2020) “The use of the shock index to predict hemodynamic collapse in hypotensive sepsis patients: A cross-sectional analysis”. Saudi Journal of Anaesthesia. 14(2):192-199

Rady M, Rivers EP, Martin G, et al. (1992) “Continuous Central Venous Oximetry and Shock Index in the Emergency Department: Use in the Evaluation of Clinical Shock”. American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 0:538–541.

Rady M, Smithline H, Blake H, et al. (1994) “A Comparison of the Shock Index and Conventional Vital Signs to Identify Acute, Critical Illness in the Emergency Department”. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 24:685–690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]