The Accident Procedure

The universal accident procedure of “ABC” is the crux of First Aid Training. Whichever course you have attended and whichever variant you have been taught (ABC, DRABC, DRSABC…) they all follow the basic concept of treating the most important things first.

The ABC acronym was coined in the 1950's by Peter Safar in his book The ABC of Resuscitation in an attempt to improve and standardize CPR training. Since then it has been adopted almost universally as the underlying principle of Basic Life Support.

ABC in First Aid

The premise is simple; If you don’t have an open airway, the casualty cannot breathe. If they are not breathing or they have difficulty breathing, that will probably kill them next through respiratory arrest. Bleeding or a failure to pump oxygenated blood (circulation) will then kill them next.

In First Aid, rather than a clinical setting, we front-load the acronym with “DR” for Danger and Response.

ABCDE in a Clinical Setting

In a clinical setting, healthcare professionals would follow the current ABCDE protocol. Danger is not considered as the setting is presumed to be safe. Response is checked later under Disability. Finally, a check for injuries is carried out under Expose.

The Problem

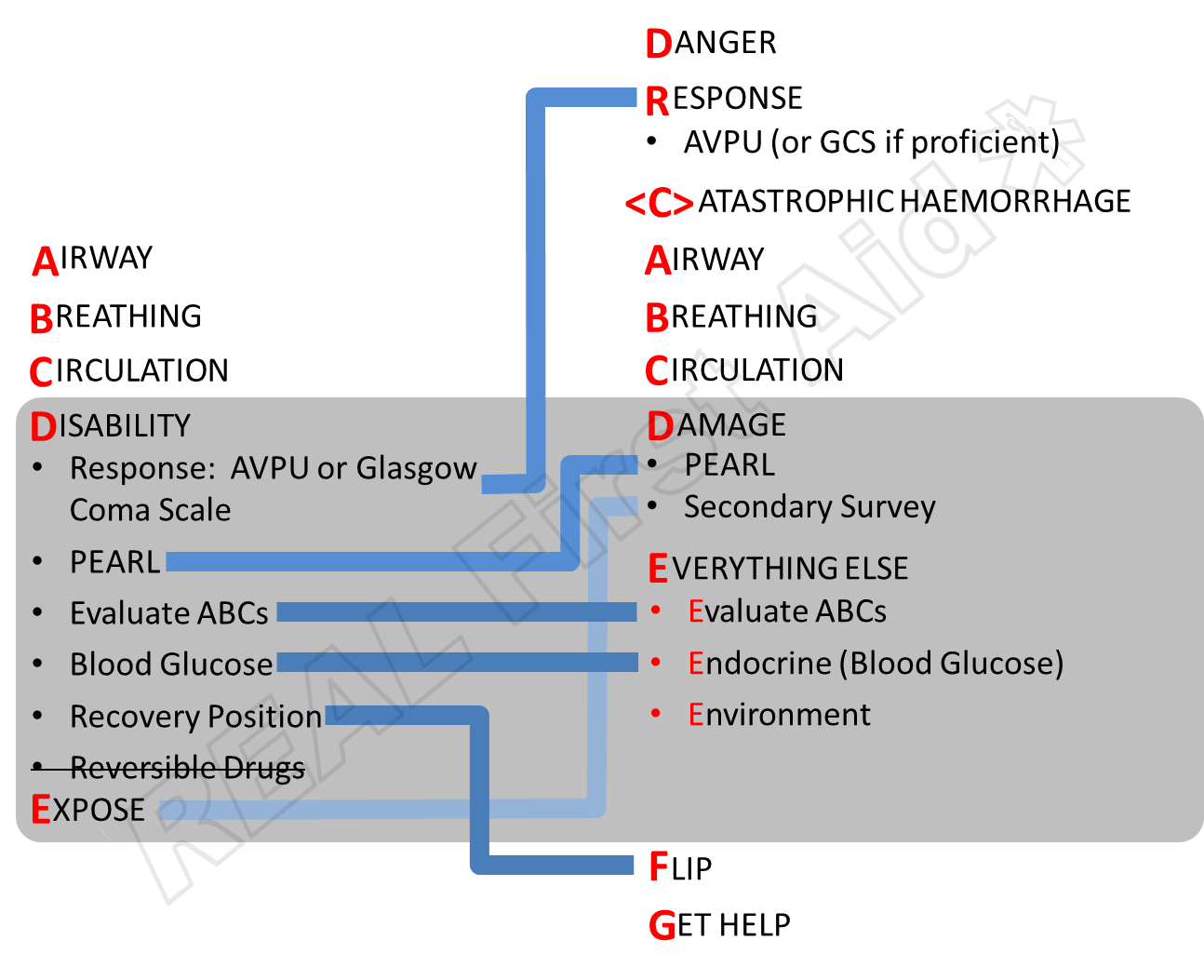

The problem is that on FREC, FPOS and other Pre-Hospital Care courses the DRABC and ABCDE protocols are hastily wedged together.

Responders are still in a pre-hospital setting, so Danger and Response are considered first.

The Disibility phase of ABCDE requires the Responder to check response and recheck ABCs which they have literally just done.

Responders are not Registered Healthcare Professionals, so some elements of Disability such as testing blood-glucose levels or understanding reversible drugs are above their scope of practice.

So we have a mish-mash of a basic DRABC married to an advanced ABCDE protocol which was designed for a clinical setting.

The REAL First Aid Accident Procedure - DR(C)ABCDEFG

The universally familiar DRABC can be extended to accommodate more advanced assessment and treatment of injuries and illnesses and consider issues of longer-term care that mirrors the ABCDE approach yet is still applicable in a pre-hospital setting.

Danger: O Minutes

You are the most important person. If immediate danger is not managed, you and the casualty may be dead in approximately 0 minutes.

Response

This does not have to be an overt check but can be done quickly on arrival or concurrently whilst checking ABC.

Catastrophic Haemorrhage: 0-5 minutes

If the mechanism of injury suggests a potential for Catastrophic Haemorrhage, now is the time to identify it and treat it. It is possible to bleed to death before airway issues become a problem.

Because not all incidents will suggest Catastrophic Haemorrhage, the C is placed in brackets to remind us to consider it, in trauma casualties where there is a mechanism of injury to suggest it, but not necessarily all casualties.

Airway & Breathing: 5 minutes

Without an open airway the casualty cannot breathe so there is no point checking the breathing until we have established the airway is both clear and open.

Without sufficient oxygen, early stages of brain damage can occur within 5 minutes (1, 2) After 9 minutes without oxygen cardiac arrest can follow (3). Most casualties do not regain consciousness after 10 minutes of asphyxia (4).

Circulation: 15-20 minutes

As well as assessing for signs of circulation, now is the time to look for bleeding if it has not been identified in <C>. It is very difficult to put a time scale on when death will follow blood loss and little data available on the time needed to apply direct pressure to life-threatening bleeding (5)

One citation (6) is that direct pressure over a bleeding wound for 15-20 minutes compresses capillaries allowing platelet aggregation and the commencement of the coagulation cascade for most wounds.

There is no point in applying direct pressure for 20 minutes if the casualty is not breathing or does not have a clear and open airway.

Damage: 0–24 hours

This is our Disability and Expose. In Damage we want to know what is wrong with them; what is Damaged? It could be physical damage i.e. injuries or it could be physiological damage; underlying medical conditions.

Haemorrhage is the leading cause of death within the first 24 hours which is why it is Circulation is prioritized above Damage, but it is followed by significant head injury, organ damage and pelvic fractures (7-16).

Using the “Head to Toe” approach, once we have stabilised Circulation issues, we start examining the casualty for Head injuries; In the same way that the ABCDE mnemonic looks at Disability after Circulation, we start with a Disability assessment straight after Circulation before moving down the body, prioritising chest, abdomen, pelvis and long bones in that order.

Everything Else: Pre-emptive

In this phase we are not looking at treating issues, rather monitoring and preventing issues.

Evaluate Vital Signs

Assessing the casualty’s vital signs can tell you whether the casualty is Big Sick or Little Sick. Evaluating the vital signs over time can tell you whether the casualty is improving or deteriorating. Identifying trends can determine whether the casualty is going into shock or developing a significant head injury, for example.

Environment

Whilst casualties can get too hot, casualties almost always become too cold. This means packaging them to prevent hypothermia.

Eaten / Endocrine

Diabetes is the most common endocrine disorder so at this stage we rule out low blood sugar levels in all casualties, not just those with diabetes.

Flip

Flip is a simile for the Safe Airway Position (or Recovery Position or Three Quarter Prone or Drainage Position or whatever else you call it) but it also means any appropriate position for the casualty. As a rule a conscious casualty will always adopt a comfortable position but some positions can make particular conditions worse.

Get Help

Getting help is sometimes best done later rather than sooner, when you have a better idea of what is going on with the casualty, when you have information worth passing on, when you know what help, if any, is needed.

What is important to remember is that any Accident Procedure is a model – a simplified, distilled version of reality designed for a ‘best fit’ of any situation. It is not 100% accurate for every situation but it is tried, tested and works for most situations most of the time.

This model also builds progressively from basic First Aid principles which candidates will be familiar with to clinical standards for those who are following a progressive pathway into Pre-Hospital Care.

Next Article: 5 Basic Vital Signs

References

Richmond, TS (May 1997). "Cerebral Resuscitation after Global Brain Ischemia", AACN Clinical Issues 8 (2).

Safar P, Behringer W. (2003) “Brain resuscitation after cardiac arrest”. In Textbook of Neurointensive Care. Edited by Layon AJ, Gabrielli A, Friedman WA. Philadelphia: WB Saunders:457–498.

Berg RA, Hilwig RW, Kern KB, Babar I, Ewy GA (1999) “Simulated mouth-to-mouth ventilation and chest compressions (bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation) improves outcome in a swine model of prehospital pediatric asphyxial cardiac arrest. Critical Care Medicine. Sep;27(9):1893-9.

Weinberger LM, Gibbon MH, Gibbon JH Jr. (1940) “Temporary arrest of the circulation to the central nervous system: pathologic effects.” Archives of Neurology and Psychiatry. 43:961-986

Charlton NP, Solberg R, Singletary N, Goolsby C, Rizer J, and Woods W. (2019) "The use of a “CPR posture” for hemorrhage control." International Journal of First Aid Education. Vol. 2, Iss. 1 , Article 6.

Larson P. (1988) “Topical hemostatic agents for dermatologic surgery”. The Journal of dermatologic surgery and oncology. 14:623-32.

Gunst M, Ghaemmaghami V, Gruszecki A, Urban J, Frankel H, Shafi S. (2010) “Changing epidemiology of trauma deaths leads to a bimodal distribution.” Proceedings (Baylor University. Medical Center) 23(4):349–354.

Baker CC, Oppenheimer L, Stephens B, Lewis FR, Trunkey DD. (1980) “Epidemiology of trauma deaths.” American Journal of Surgery. 140(1):144–150.

Demetriades D, Kimbrell B, Salim A, Velmahos G, Rhee P, Preston C, Gruzinski G, Chan L. (2005) “Trauma deaths in a mature urban trauma system: is “trimodal” distribution a valid concept?”. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 201(3):343–348.

Demetriades D, Murray J, Charalambides K, Alo K, Velmahos G, Rhee P, Chan L. (2004) “Trauma fatalities: time and location of hospital deaths”. Journal of the American College of Surgeons 198(1):20–26.

Sauaia A, Moore FA, Moore EE, Moser KS, Brennan R, Read RA, Pons PT. (1995) “Epidemiology of trauma deaths: a reassessment”. Journal of Trauma. 38(2):185–193.

Meislin H, Criss EA, Judkins D, Berger R, Conroy C, Parks B, Spaite DW, Valenzuela TD. (1997) “Fatal trauma: the modal distribution of time to death is a function of patient demographics and regional resources.” Journal of Trauma. 43(3):433–440.

Trunkey DD, Lim RC. (1974) “Analysis of 425 consecutive trauma fatalities: an autopsy study.” Journal of the American College of Emergency Physicians. 3(6):368–371.

Potenza BM, Hoyt DB, Coimbra R, Fortlage D, Holbrook T, Hollingsworth-Fridlund P. (2004) “The epidemiology of serious and fatal injury in San Diego County over an 11-year period.” Journal of Trauma. 4;56(1):68–75.

Cothren CC, Moore EE, Hedegaard HB, Meng K. (2007) “Epidemiology of urban trauma deaths: a comprehensive reassessment 10 years later.” World Journal of Surgery. 31(7):1507–1511.

Shackford SR, Mackersie RC, Holbrook TL, Davis JW, Hollingsworth-Fridlund P, Hoyt DB, Wolf PL. (1993) “The epidemiology of traumatic death. A population-based analysis.” Archives of Surgery. 128(5):571–575.