Crush Injury

6th September 2017 updated 3rd March 2024

UK First Aid at Work protocols recommend not removing the entrapped casualty if they have been entrapped for more than 15 minutes because of the consequences of a loss of circulation to a limb and the build up of ‘toxins’.

But we also advocate that tourniquets can safely be applied for hours.

No wonder there is confusion on the pre-hospital management of both Crush Injury and tourniquet application.

Traditional First Aid Teachings:

When a limb becomes trapped (be it a tourniquet or entrapment) there is neither fresh supply of oxygen nor the removal of waste products due to the lack of circulation. What is traditionally taught is that these waste products accumulate to a toxic level and, should the limb be released, the waste products are released into the circulatory system and pumped to the heart which can cause cardiac arrest and IMMEDIATE DEATH!

As such, traditional UK First Aid guidelines including the current 10th edition of the Voluntary Ambulance Services First Aid Manual (1) state "If the casualty has been crushed for more thank 15 minutes…leave them in the position found. Offer comfort and reassurance."

This

Is

nonsense.

What is Crush Syndrome?

Crush syndrome refers to the complications following prolonged entrapment; the cause may be building collapse, fallen debris, vehicle entrapment, or simply the continued pressure exerted by the immobile casualty’s own body weight. (2-6)

Crush injury occurs when a body part is subjected to a high force or pressure, usually after being squeezed between two heavy objects. As a result of muscular compression, muscle cells (myocytes) are damaged, followed by the release of intracellular constituents into the systemic circulation. The process, called rhabdomyolysis, causes systemic organ dysfunction, such as acute renal failure, and is then called crush syndrome. (7-9)

The Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh’s Faculty of Pre-Hospital Care’s consensus view is (2):

“A crush injury is a direct injury resulting from crush. Crush syndrome is the systemic manifestation of muscle cell damage resulting from pressure or crushing”.

The likelihood of developing acute crush syndrome is directly related to the compression time, therefore victims should be released as quickly as possible, irrespective of how long they have been trapped. (2,3)

The principle complications of crush syndrome are the build up of toxins – rhabdomyolysis – and the lesser known, compartment syndrome. In this article we will look at both.

Tourniquets

The same mechanism of action occurs whether the limb is trapped or a tourniquet has been applied but the evidence for tissue damage points toward the order of magnitude of hours, rather than minutes (10-12).

Tourniquet use for less than 2 hours has proven safe. Tourniquets left in place for longer than 2 hours risk significant ischemic injury and should be converted.

Tourniquets in place longer than 6 hours should be left in place with an increased need for limb amputation.

Rhabdomyolysis

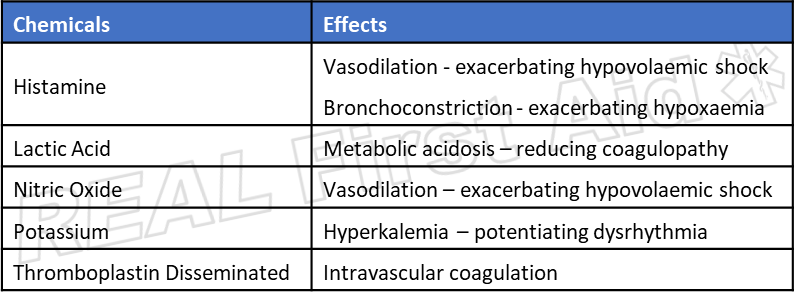

As increasing pressure caused by a restriction (be it entrapment or a tourniquet) reduces circulation to the area the decrease in oxygen requires the cells to switch from aerobic respiration to anaerobic respiration. In this state cells attempt to produce energy from CO2 which generates large amounts of lactic acid and other damaging substances:

Continued pressure exerted on muscle tissue stretches the cell membranes, increasing their porosity allowing, sodium, calcium and water into the sarcoplasm (equivalent to the cytoplasm of other cells) trapping extracellular fluid inside the muscle cells. (13)

Calcium enters the cell, in exchange for intracellular sodium. Large quantities of free calcium ions trigger persistent contraction, resulting in energy depletion and cell death. (14)

In addition to the influx of these elements into the cell, the cell releases potassium and other nephrotoxic (damaging to the kidneys) substances such as myoglobin, phosphate and urate into the circulation. (13)

The results of this can lead to hyperkalaemia (which may precipitate cardiac arrest), hypocalcaemia, metabolic acidosis and Acute Kidney Injury (formerly known as acute renal failure). Acute Kidney Injury is due to a combination of: (2)

hypovolaemia with subsequent renal vasoconstriction

metabolic acidosis

The productions of myoglobin, urate and phosphate block or damage the nephrons of the kidneys.

Recognition of Rhyabdomyolysis

The clinical diagnosis of rhabdomyolysis is the level of creatine kinase in the blood (15) which is impractical in a pre-hospital environment. High levels of Haemoglobin may be revealed in a urine test strip. (16)

A retrospective analysis of 372 cases of crush injury (3) found “the most informative predictors of renal failure were elevated pulse rate and abnormal urine colour, which relate directly to the pathophysiology. The other major risk factor, delayed rescue (≥3 hours from time of injury to rescue), may be important because delayed treatment can exacerbate the severity of crush injuries”.

After Aoki et al (2007)

If ECG is available progressive hyperkalemia can result in identifiable changes in the ECG (17, 18)

Mild hyperkalemia (6-7 mmol/l) – peaked T waves.

Moderate hyperkalemia (7 – 8 mmol/l) – flattened P wave, prolonged PR interval, depression of ST segment, peaked T wave.

Severe hyperkalemia (8 – 9 mmol/l) – atrial standstill, prolonged QRS duration, further peaking T waves.

Life-threatening hyperkalemia (>9 mmol/l) – sine wave pattern.

Maintain a high suspicion of rhabdomyolysis if:

Casualty has been entrapped for more than 3 hours or

abnormal urine colour and a pulse rate of 120 bpm

Elevated T wave if ECG is available

Treatment (2)

Assessment of <C>ABC

Administration of High Flow Oxygen

Assessment and of other bleeding wounds

Exposure should be as limited as possible especially in hostile or cold weather conditions.

Assessment of distal neurovascular status is essential if exposure is to be kept to a minimum.

The patient should be released as quickly as possible, irrespective of the length of time trapped.

Tourniquets: The use of tourniquets has a theoretical role in the management of these patients however there is currently no available evidence to support this.

There is no evidence to support the use of amputation as a prophylactic measure to prevent crush syndrome.

Original Source: NHS Choices

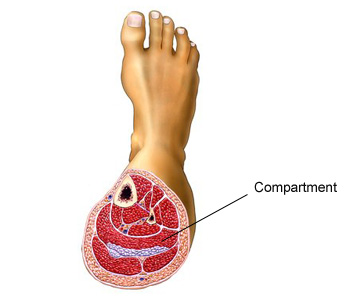

Compartments are groupings of muscles, nerves, and blood vessels in limb, surrounded in a tough, non-elastic membrane called a fascia.

Compartment syndrome develops when swelling or bleeding occurs within a compartment. Because the fascia does not stretch, this can cause increased pressure on the capillaries, nerves, and muscles in the compartment, restricting blood flow, oxygen perfusion and waste removal leading to tissue ischaemia.

Compartment syndrome may also occur from the inappropriate application of tourniquets or as a consequence to crush injury: In both cases, if the external force applied to the limb is greater than the diastolic blood pressure, but less that systolic, arterial blood continues to be introduced to the limb but returning blood cannot escape, increasing pressure within the limb and reducing oxygen perfusion.

Tourniquet based models suggest muscles can tolerate 3-8 hours of ischemia before developing necrosis. (19-23) however, compartment syndrome-induced ischemia muscle degeneration may be more common and severe than tourniquet-induced ischemia. (24, 25)

In the above image, the right leg does not look as visibly disturbing as a traumatic injury, simply ‘swollen’ and without an overt mechanism of nijury, rather benign. Compartment Syndrome is a limb - and sometimes life - threatening condition.

Recognition of Compartment Syndrome

The 5 (or 6) Ps of Compartment Syndrome are often used as a diagnosis:

Pain

Pallor

Paresthesia - numbness or tingling

Pulse

Paralysis (or Paersis - weakness)

(Poikilothermia – inability to regulate temperature i.e. different temperatures between the affected limb and non-affected limb)

This traditional method may not be accurate as they may present as any soft tissue or bone injury and all except pain are present only in late stages, by which time the affected limb is no longer viable. (26,27)

Statistical analysis of clinical findings suggest that one indicator has a low threshold, as little as 19%, while the presentation of three or more are significantly more accurate at the expense of delayed recognition. (28)

After Ulmer (2002)

Ulmer (2002) summarises (28)

“The absence of the findings for compartment syndrome was more helpful in excluding the diagnosis than was the presence of the findings for establishing the diagnosis.”

As such we recommend assuming a high suspicion of compartment syndrome especially in crush injuries and long-bone fracture unless the 5 Ps are absent.

Treatment

There is no pre-hospital treatment of Compartment Syndrome - recognition is important for communicating to the recieving hospital.

Do NOT elevate the limb - this will exacerbate ischemia

If Compartment Syndrome is suspected, evacuate to hospital as soon as possible.

References

St Johns Ambulance, St Andrews First Aid and British Red Cross (2020) First Aid Manual. 11th Edition. Dorling Kindersley. London. p.120

Greaves I, Porter K, Smith JE. (2003) “Consensus Statement On The Early Management Of Crush Injury And Prevention Of Crush Syndrome” Journal of the Royal Army Medical Corps. 149: 255-259

Aoki N, Demsar J, Zupan B, Mozina M, Pretto EA, Oda J, Tanaka H, Sugimoto K, Yoshioka T and Fukui T. (2007) “Predictive Model for Estimating Risk of Crush Syndrome: A Data Mining Approach”. The Journal of Trauma, Injury, Infection, and Critical Care. April. 62 (4) 940-945

Brown AA and Nicholls RJ, (1977) "Crush syndrome: A report of 2 cases and a review of the literature". British Journal of Surgery. 1977;64(6):397-402

Burns K, Cone DC, Portereiko JV. (2010) "Complex extrication and crush injury". Prehospital Emergency Care. 14(2):240-4

Jagodzinski NA, Weerasinghe C and Porter K. (2010) "Crush injuries and crush syndrome - A review. Part 1: The systemic injury". Trauma. 12(2):69-88

Smith J, Greaves I. (2003) “Crush injury and crush syndrome: a review”. Journal of Trauma. 54:S226 –S230.

Better OS. (1990) The crush syndrome revisited (1940 –1990). Nephron. 55:97–103.

Michaelson M. (1992) “Crush injury and crush syndrome”. World Journal of Surgery. 16:899 –903.

Drew B, Bird D, Matteucci M, Keenan S. (2015) “Tourniquet conversion: a recommended approach in the prolonged field care setting”. Journal of Special Operational Medicine. 15(3):81–85.

Shackelford SA, Butler FK, Jr., Kragh JF, Jr., Stevens RA, Seery JM, Parsons DL, Montgomery HR, Kotwal RS, Mabry RL, Bailey JA. (2015) “Optimizing the use of limb tourniquets in tactical combat casualty care: TCCC guidelines change 14-02.” Journal of Special Operational Medicine. 15(1):17–31.

Drew B, Bennett BL, Littlejohn L. (2015) “Application of current hemorrhage control techniques for backcountry care: part one, tourniquets and hemorrhage control adjuncts.” Wilderness and Environmental Medicine. 26(2):236–245.

Better OS. (1999) “Rescue and salvage of casualties suffering from the crush syndrome after mass disasters”. Military Medicine. 164: 366-9.

Brumback RA, Feeback DL, Leech RW(1992) “Rhabdomyolysis in childhood: A primer on normal muscle function and selected metabolic myopathies characterized by disordered energy production”. Pediatric Clinics of North America. 39: 821-858,1992

Chavez, LO; Leon, M; Einav, S; Varon, J (2016). "Beyond muscle destruction: a systematic review of rhabdomyolysis for clinical practice." Critical Care. 20 (1): 135.

Vanholder R; Sever MS; Erek E; Lameire N. (2000). "Rhabdomyolysis". Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 11 (8): 1553–61

Feehally J, Floege J, Johnson RJ(2007) Comprehensive clinical nephrology. 3rd Ed. St Louis. Mosby.

Goldberger, A(2006) Clinical Electrocardiography: A simplified approach. 7th Ed. St. Louis. Mosby.

Haljamae H, Enger E. (1975) “Human skeletal muscle energy metabolism during and after complete tourniquet ischemia”. Annals of Surgery. 975;182(1):9-14.

Heppenstall RB, Scott R, Sapega A, Park YS, Chance B. A(1986). “Comparative study of the tolerance of skeletal muscle to ischemia - Tourniquet application compared with acute compartment syndrome”. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 68(6):820-8.

Miller SH, Price G, Buck D, Kennedy TJ, Graham WP 3rd, Davis TS. (1979) “Effects of tourniquet ischemia and postischemic edema on muscle metabolism”. Journal of Hand Surgery. 4(6):547-55.

Sapega AA, Heppenstall RB, Chance B, Park YS, Sokolow D. (1985) “Optimizing tourniquet application and release times in extremity surgery. A biochemical and ultrastructural study”. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 67(2):303-14.

Day LJ, Bovill EG, Trafton PG. (1991) “Orthopedics”. In: Way LW, editor. Current surgical diagnosis & treatment. 9th ed. Norwalk. Lange; p. 1038.

Heppenstall RB, Scott R, Sapega A, Park YS, Chance B. A(1986). “Comparative study of the tolerance of skeletal muscle to ischemia - Tourniquet application compared with acute compartment syndrome”. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 68(6):820-8.

Vaillancourt C, Shrier I, Vandal A, Falk M, Rossignol M, Vernec A, Somogyi D. (2004) “Acute compartment syndrome: How long before muscle necrosis occurs?” Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine. 6:147–154

Duckworth AD, Mcqueen MM. (2011) “Focus on diagnosis of acute compartment syndrome”. British Editorial Society of Bone and Joint Surgery.

Ryan M. Taylor, Sullivan MP, Mehta S. (2012) “Acute compartment syndrome: obtaining diagnosis, providing treatment, and minimizing medicolegal risk”. Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine. Sep; 5(3): 206–213.

Ulmer T. (2002) “The clinical diagnosis of compartment syndrome of the lower leg”. Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma. 16(8):572-7